Read the article

here.Tomer is a senior meteorological scientist at WindBorne, working on evaluating weather model forecasts for weather phenomena such as cold outbreaks, heat waves and tropical cyclones, and finding new ways to integrate forecast uncertainty into balloon operations. Outside of work and being a weather enthusiast, Tomer enjoys running, hiking, traveling, and computer programming.

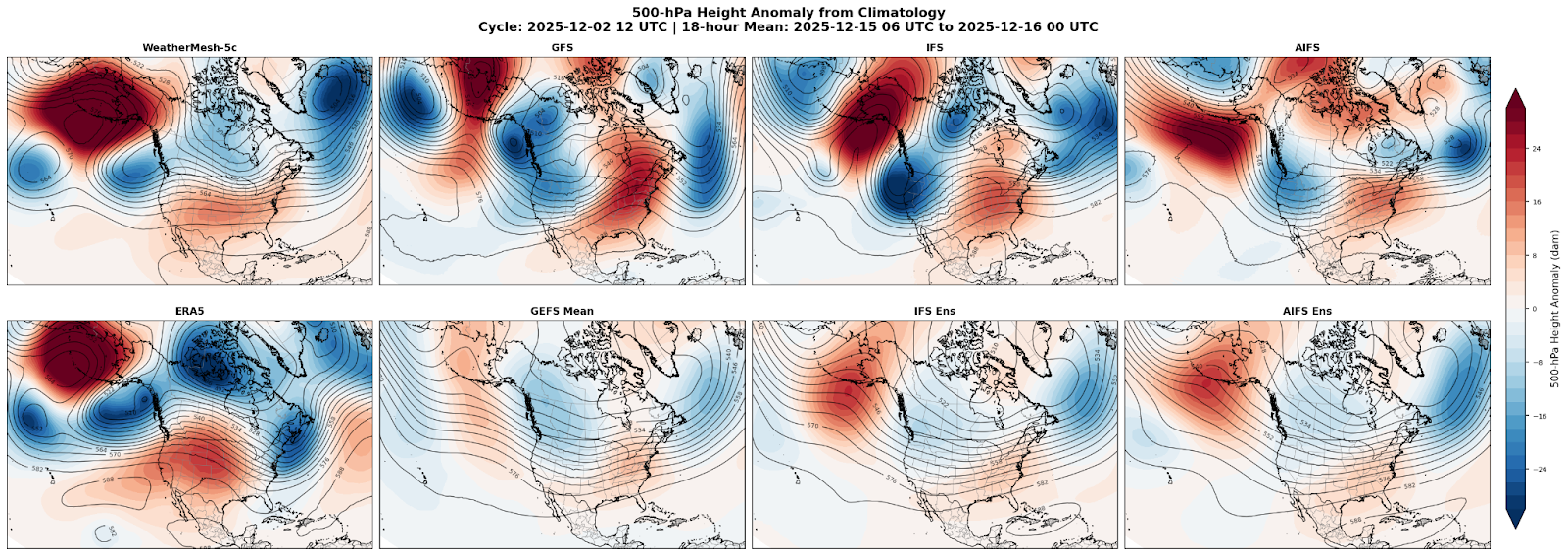

On December 2nd I was tasked with making a middle of the month forecast for temperature anomalies in the densely populated eastern U.S. My first instinct was to look at the often reliable IFS and its 50-member ensemble, from ECMWF. Both versions showed a signal for a trough in the western U.S., and a ridge with above-average temperatures in the eastern U.S.

Any good meteorologist knows that a quality forecast requires the assessment of multiple model suites. Forecasts are tricky and it’s best to review all available data before making any decisions. I reviewed the following models for the same timeframe:

- Deterministic models (NOAA’s GFS, ECMWF’s physics-based IFS and AI-based AIFS): showed a western U.S. trough with below-average temperatures, and an eastern U.S. ridge with above-average temperatures

- Ensemble models (31-member GEFS ensemble, 50-member AIFS ensemble, 50-member IFS ensemble): noticeably less extreme than their deterministic counterparts, as ensemble means tend to smooth extreme signals out, but still signaled a West Coast trough and an East Coast ridge

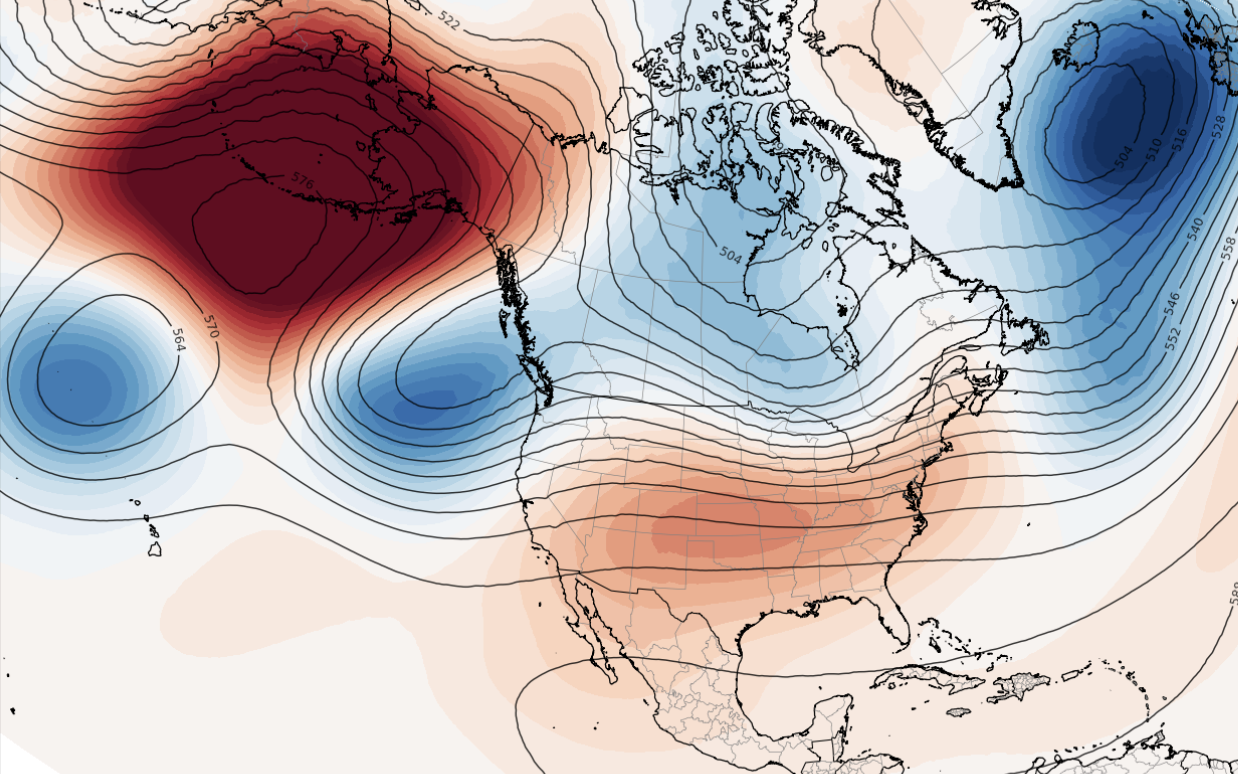

All 3 major suites did not flag any major cold air outbreaks of concern in the East Coast, but WeatherMesh didn’t agree. WeatherMesh signaled a weak ridge in the West Coast and weak trough near the Great Lakes. As it turned out, WeatherMesh was on the right track. While the models missed the presence of a deep trough in the East Coast, WeatherMesh was the only model to not show a ridge in the East Coast nor a trough in the West Coast.

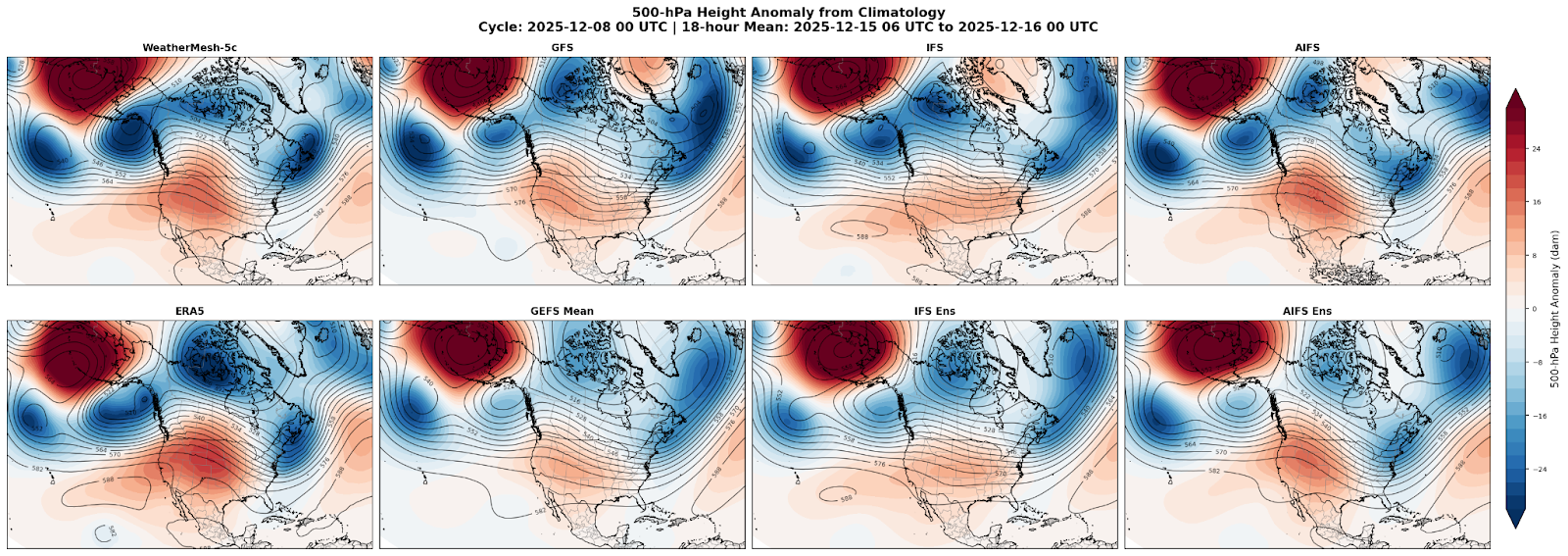

Now let's fast-forward a few days, it’s December 8th, and while there are still some differences between models with just how deep the trough is over the US East Coast, all of these models are now in agreement on a potentially significant cold air outbreak in the northern and eastern U.S in mid-December. So, what changed over a few days?

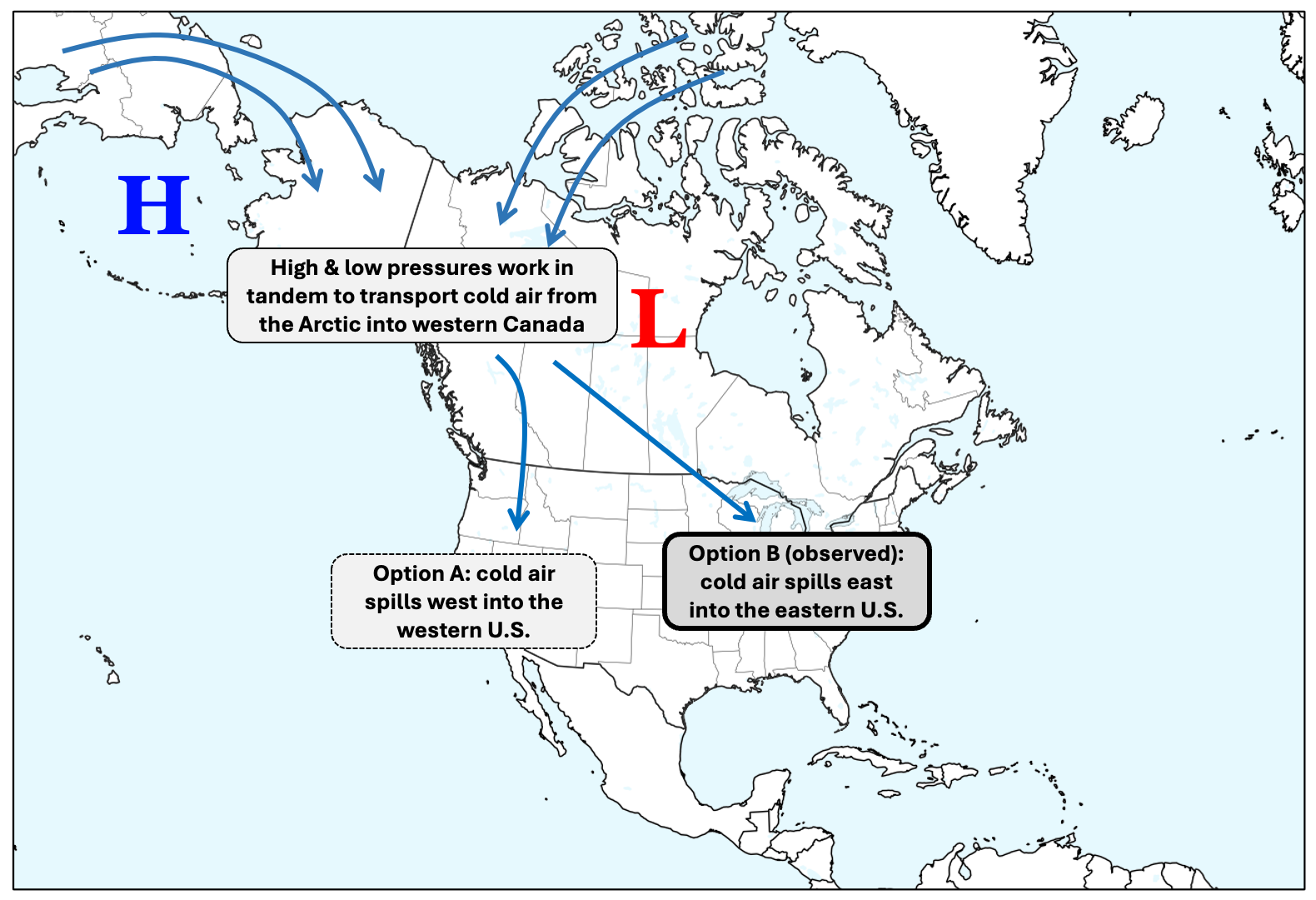

For a simplified explanation, we need to look upstream – in Alaska.

Much of the last month has been characterized by a block, or a near-stationary ridge of high pressure aloft separated from the jet stream, over the Bering Sea. Strong northerly flow to the east of this block has been routinely transporting frigid Arctic air southward into Canada, but earlier models incorrectly directed that cold air towards the western U.S.

WindBorne’s WeatherMesh-5c avoided the inaccuracies of both physics-based IFS model and AI-based AIFS model - where those models directed the cold anomalies too far west, WeatherMesh correctly maintained a Hudson Bay vortex and reinforced the colder than average pattern over the northern and eastern U.S.

So what does it all mean?

AI models are a relatively new addition to the weather forecasting sphere, and while they still operate as a sort of a “black box”, they have proven to be adept in producing medium-to-long range forecasts vs. traditional physics-based models, in part due to improving upon systematic model biases. Even ECMWF’s AI-based AIFS model and ensemble failed to see this cold outbreak at longer lead times.

WeatherMesh’s ability to detect this event points to a fundamental shift in how weather-dependent sectors can operate. For energy and power markets, we are seeing how this kind of early insight doesn’t just improve day-to-day forecasting but can undergird risk management strategies, infrastructure planning, and market positioning. The implications extend beyond a single weather event. Think: better resource allocation, reduced operational costs, improved grid resilience, and efficient long-term capital planning.

In the meantime, we will continue to monitor the ongoing weather for an expected moderation in the cold pattern in the eastern 2/3rds of the US heading into late December, and just how much temperatures will actually warm in the northern part of the U.S. vs. what models currently expect.